- Home

- Mike Revell

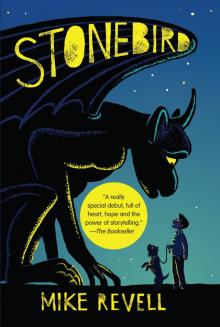

Stonebird Page 8

Stonebird Read online

Page 8

If you tell anyone about what happened yesterday, you’re dead.

I can’t decide if he means I should keep my lips sealed about our parents fancying each other, or about them trying to force us to hang out . . . or about one of his grandparents having a demon like my grandma’s.

I suppose it’s best not to say anything at all.

It’s weird what sad things do to people. Mom is down all the time, and Matt is angry all the time, and me . . . I’m not angry. I’m not sad.

I don’t know what I am.

We’re sitting in the circle again.

The egg’s on its way around. Mrs. Culpepper nods when Ruth tells a story about her swimming championships and smiles when John describes the robot he’s making with his dad.

But I’m not really listening to them, because next up it’s Matt. And look at him. Look at his eyes. Why won’t he stop staring at me? His mouth twitches and his lips pull back, revealing yellow teeth.

The egg moves on to him and he holds it and still he’s not taking his eyes off me.

“My granddad showed me how to play chess last night,” he says, and finally his gray eyes leave me and roam around the rest of the class. Everyone’s waiting on his words. “But not the normal kind. He plays it through the mail with people from Russia . . .”

As he explains it, even I have to admit it’s a cool story.

But it’s a lie. It’s got to be a lie. Because he was at the retirement home yesterday, just like I was. Everyone’s watching him, but they’re not watching watching him; they’re just looking without really seeing. They’re letting the words wash over them and picturing the scene and smiling as if they’re playing chess themselves.

Matt’s knee jerks up and down as he talks. His eyes never stay in one place. It’s a lie. It’s got to be.

Just like my story. I think back to last week, when I told them about Stonebird. I lied too, didn’t I? I had seen him and he did move, he must have moved, but how do I know what he did or where he went? I made up a story, a lie, and it felt good.

Maybe all stories are lies, in a way.

But I lied because I couldn’t think of anything to say.

I lied because it helped to explain things.

Matt’s not helping to explain things at all.

By the time the egg gets to me, I’m ready. Stonebird is in my mind as soon as the warm marble touches my hand. I wait for a moment, tracing the lines of the light-blue veins in the stone. I’m not trying to make everyone wait or anything, just getting everything in order in my head.

When I look up, they’re glaring at me. Matt and his friends. There’s no way he’s told them what happened, but even so, their eyes are hot and angry.

If you tell anyone about what happened yesterday, you’re dead.

His voice rings in my head, and for the first time I realize I can get him back. Really get him back, I mean. If he went to that much trouble to warn me off, then he must really not want anyone to know about our parents.

It would be so easy . . .

I start to speak. Last night I made a friend . . . I wait for his reaction. His head snaps around and his hands twitch, as if they’re itching to reach out and strangle me.

But I’m not brave enough to do it. I want to, but the look in his eyes is enough to smack the thought out of my head and bring me back to the real world. I would feel great for what, twenty minutes? And then the bell would go, and everyone would leave. Everyone apart from Matt and his friends.

His hand moves, a quick thumb line across his neck.

Then it’s back, resting on his lap.

I pass the egg from hand to hand, licking my lips.

“Go on,” says Matt. “Who’s this friend?”

“Matthew!” says Mrs. Culpepper, turning to him. “Only the person with the egg is allowed to talk.”

“Sorry.”

She scowls at him, then turns back to me.

The gargoyle, I say, automatically.

Out by the church. It was on the roof, sitting in the moonlight. I only noticed it because its shadow reached all the way across the road.

Wings and horns and spikes and claws.

The wind howled around me. Its huge wings reared up. Blood pounded in my ears. I tried to run, but I couldn’t move. I looked around for somewhere to hide, for something to help, but where could I go?

And suddenly there it was in front of me.

The gargoyle didn’t speak. I don’t think it can speak.

But it stared. Its eyes were the size of fists in its massive head, and they shone the color of the stars.

I still couldn’t move—it was like I’d grown from the ground, like I had roots holding me in place. The gargoyle didn’t move either. Just looked at me.

Goose bumps tingled on my neck.

Its head tilted sideways, and my stomach curled up inside me.

“What do you want?” I said, but my voice was a squeak—I thought it was going to kill me. I knew it was going to kill me. Why else had it flown down? Why else was it standing over me in the middle of the street?

“What did it do?” someone says. I don’t know who. I’m staring at the egg, seeing the story in it, living it, breathing it.

“Shh!” says Mrs. Culpepper.

But it didn’t kill me.

It turned and sprang up, and its wings thumped and thumped at the air, taking it higher into the sky.

I chased after it, around the bend, down the lane.

Heart hammering, I chased it. Until—

“Let me guess,” says another voice, and this time it’s Matt. “It flew off. Great story. You don’t expect us to believe this, do you?”

“Shhh!” hisses Mrs. Culpepper. “I won’t tell you again.”

I need to think of something. A test that will prove I’m right about Stonebird. Something more than just vanishing or protecting me.

But my mind fogs up again. Matt’s thrown me off.

The class is watching me, all of them, eyes wide, waiting, waiting . . .

And—um . . .

And it . . .

It landed in my garden. And it just sort of—fixed things.

That’s how it ends. With a gargoyle in my garden fixing things.

And with the class sniggering around me.

I hold the egg for a moment more, not daring to meet Matt’s smirk or the look on Mrs. Culpepper’s face. Then, cheeks burning, I pass it on.

19

When the bell goes at three fifteen, everyone gets up to leave, but Mrs. Culpepper calls me over to her desk. She’s flicking through the drawings we did the other day. I wait for her to speak, but she doesn’t, not until everyone’s left.

“You’ve found him, haven’t you?” she says, without looking up.

“Sorry?”

“Stonebird.”

All the air rushes out of the room. I glance back to make sure no one can hear us, but we’re alone. Everyone else is sprinting into the playground, eager to get home.

“It’s a remarkable picture,” she says, holding up my drawing. “You have your grandmother’s talent, you know.”

How does she—

Then I remember the flowers in Grandma’s room. Mrs. Culpepper knew about Grandma even before I said anything, and at first I thought Mom must have told the teachers, but what if she never did?

“It was you,” I say. “You’re the one who’s been visiting her.”

“Yes,” Mrs. Culpepper says, and for the first time a hint of sadness creeps into her eyes. She opens a desk drawer and takes out the egg. “Do you recognize this? Have you seen it anywhere before? Other than in class, I mean.”

“No,” I say slowly.

Mrs. Culpepper takes a deep breath. “Can I tell you a story, Liam? Believe it or not, it starts right here in Swanbury, when I was a little girl, no older than you. I had a teacher by the name of Mrs. Williams—”

I can’t believe it. “My grandma?” I say.

“Indeed. She did the most wonderful

thing with the class. Every week, before English, she would sit us down in a circle and encourage us to tell stories. This egg was hers, you see. I seem to remember her telling me that her father made it for her, out of a piece of Parisian rock. At any rate, she was always very careful with it. She called it her magic egg, and everyone loved it, although I don’t think anyone really believed that it was magic. I know I didn’t. Not at first, anyway. But then, one night, something changed.”

“I didn’t have what you might call the perfect family. My father—well, he was never the same after the War. Without the danger and the noise and the orders, he didn’t know how to live. He was falling apart, Liam, and because of that my family was too.”

I give her a look that says, I know how that feels, because Mom keeps crying and Jess is skipping school and it feels like we’re all falling apart too.

“If things ever got too bad, I used to run away. But I didn’t have anywhere to go, so do you know what I did? I turned to your grandmother. She took me in every time I knocked on her door, and we’d sit down with this egg, and she told stories about a gargoyle called Stonebird who had looked after her since she was a child. She said he’d look after me too.”

“And he did?” I say.

“He did. Every time.” She holds up the egg and turns it under the light. “She gave this egg to me when I finished school. She said I needed it more than her. And I’ve cherished it ever since.”

That doesn’t sound like something a killer would say.

I check Mrs. Culpepper’s eyes to see if she’s lying, but they’re steady, locked onto me.

“When I heard what had happened to her, how she was suffering with dementia, I thought somehow I’d be able to help. But of course it’s not just her who has to deal with it, is it? It’s you and your family too, and everyone who ever held her close in their heart.”

I don’t know what to say to that, so I let my thoughts drift back to Stonebird.

If what Mrs. Culpepper is saying is true, then—

I was right.

A million questions explode in my mind.

How can Stonebird be real? How can any of this be happening?

“Anyway,” Mrs. Culpepper says, standing up, “I’ve kept you here long enough. Run along now. It doesn’t do to be trapped in school when there’s fresh air to be had.”

I get up to leave, but Mrs. Culpepper calls after me—

“Liam? Remember what I said. Gargoyles are wonderful things. But be careful. They can be dangerous too.”

20

Mom’s waiting for me after school.

I’m so busy thinking about Mrs. Culpepper and Stonebird that I almost walk right past her. She has the car with her, parked outside the post office.

“Mom?” I say. “What’s going on?”

“I’m afraid Grandma’s in a bad way,” she says. “I’m going to have to go in again to see her. Jess is out with her friends, and I thought . . .” She stops, and makes the face where her eyebrows shoot up and her mouth zigzags. She’s worried about something.

“What?” I say, and even as she opens her mouth, I know what’s coming.

Because it’s just hit me.

It wasn’t random talk, back in the retirement home. It was real.

“I said I’d drop you around your friend’s house. Around Matt’s. Just for a bit!” she adds, when she sees my face.

My jaw’s practically on the floor. I mean, ants could crawl into it, it’s hanging so low. I knew it was coming, but only because it’s so crazy that it had to happen. I don’t realize I’m shaking my head, but I must be, because Mom says—

“Why are you shaking your head? What’s wrong?”

“He’s not my friend, Mom.”

“Oh, Liam.” She gets in the car and shuts the door behind her. I walk around to the passenger side but don’t get in. There’s an electric whirr as the window slides down, and Mom says, “Are you coming?”

Sighing heavily, I flop into the seat, making a massive show of it. I don’t even know why—it’s just . . . I bet Jess isn’t even out with friends. She’s probably meeting Ben again, and why do I have to go around to Matt’s anyway?

“Because you do,” says Mom, and I look away—I didn’t realize I’d spoken out loud. “It’s very nice of Gary to offer.”

Why is she so obsessed with Gary?

I wish I could just come out and ask if they’re going out, but I’m scared of what the answer’s going to be. I guess it wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world if Mom and Gary did get together. He seems all right really.

But if they ever got married, Matt would be my stepbrother.

Maybe it would be the worst thing in the world after all.

“I could come with you!” My voice is squeaky and desperate. “I could see Grandma with you!”

Mom smiles at that but doesn’t say anything. Not at first. I wait and wait, but the only sound is the chitter and groan of the engine springing to life.

“No. Not this time, I don’t think. I’m afraid she’s in a really bad way. I don’t want you to—it might put her out, I mean, having too many people there. I won’t be long. I’ll be back to pick you up in no time.”

We go to the supermarket so Mom can pick up some flowers for Grandma; then she drops me off at Matt’s. His house is on the edge of the village, on a hill that runs down past the sports field. We pull into a tree-lined drive, and the pebbles crackle under the wheels of the car. In an open garage at the end there’s an ancient-looking motorbike and one of those old Minis parked next to it. Mom turns the car around and stops to give me a kiss.

“Don’t worry,” she says. “I won’t be long. Please be nice to Matt. He seems lovely.”

Oh yeah. Really lovely.

I’ve barely shut the door when the car trundles off and out of the drive and away.

It’s strange that Grandma’s got so bad so suddenly. I wonder how she looks, lying in her bed . . . how it’s possible to look any worse than she did last time.

When I found Stonebird lying forgotten in the church, I felt sorry for him. But at least he won’t wither and rot. Not for a long time. At least he won’t forget. What’s the point in living, when you’re going to forget everything anyway?

Crunch crunch crunch. I walk up to Matt’s front door. There’s a basketball hoop on the wall beside it, but no net. Squiggly crackly glass makes it impossible to see through the door. I ring the bell, and a dark shape approaches.

“Hiya, Liam,” says Matt’s dad, opening the door. “Matt’s just upstairs, playing on his GamesBox, or whatever it’s called.”

He opens the door wider so I can come in.

Happy faces grin down from the walls. Photos of Matt and his dad and a woman who must be his—

His mom.

She’s got long blonde hair and a smile that looks warm and happy. But if this is his mom, then why is Gary being so friendly with my mom? And where is she? Matt’s never spoken about her, and she’s definitely never there at school. Maybe they’re divorced. Or maybe—

I feel horrible thinking it, but maybe she’s dead.

I shiver at that.

“Thanks,” I say, snapping back to the moment and glancing away guiltily.

“Feel free to go up. I’m just finishing up a bit of work, so dinner will be a little while, I’m afraid. It’s been a bit hectic since . . .”

He trails off and his eyes go foggy like Mom’s did for a while after Dad left. I stand there waiting for him to say something, but he doesn’t, so after a while I brace myself and head upstairs.

As soon as I reach the landing, I can hear the sound of guns popping and bombs exploding. I knock three times on Matt’s door, but he doesn’t answer. The gunfire gets cut off by silence, though, so I know he’s heard me. I can’t believe I’m about to walk into his room. My heart’s beating as loud as the Xbox. I wait and wait, but it’s clear he’s not going to say anything, so I open the door and poke my head in.

It’s pure black, Mat

t’s room, and covered in posters of cars and rappers. He’s sitting on the bed clutching the controller, but as soon as I step inside, he’s up and bounding across the room.

He shoves his hand in my face.

“See this?” he says, pointing to the edge of his desk. He runs his hand in a line from wall to wall. “This is a line. You don’t cross it. You get me?”

“I get you.”

“Good.”

He slouches back and carries on playing Call of Duty. There’s nowhere to sit, so I just kneel on the floor. Mom would never let me have an all-black room. Or play CoD.

“Is this the latest one?” I ask.

“What do you think?”

His character ducks behind an exploded tank, fires a shot over the top, hides again. Planes roar through the sky above him.

“You’re so lucky your dad lets you play on this.”

His mouth tightens, and his thumbs move over the controller in fast-forward flicks. The soldier on-screen swaps an empty M16 for an RPG launcher and fires a rocket into the window of a burning building. He sprints out from behind the tank and rushes forward over ditches and barbed wire and—

Pat-pat-pat.

Three bullets and the screen’s red, and now Matt’s throwing down the controller.

“You made me do that,” he says.

Then he falls back on the bed, puts his hands behind his head.

Somewhere I can hear an old grandfather clock. I listen to the minutes ticking away until BONG BONG BONG BONG it strikes four o’clock.

The clock reminds me of his story earlier today.

Something rises inside me, and suddenly it’s so tempting to ask him, to bait him . . .

He’s not going to fight me here, surely . . . not with his dad downstairs.

“Why did you lie?” I say.

“What?”

“Why did you lie? Earlier today, with the egg? When you told your story—why did you lie?”

He doesn’t sit up, doesn’t even move. “I didn’t.”

Tick-tock, tick-tock, tick-tock.

“You said your granddad showed you how to play chess.”

Stonebird

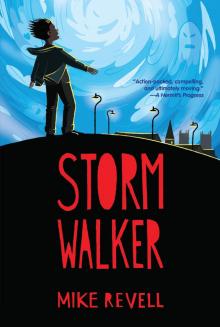

Stonebird Stormwalker

Stormwalker